PU PAU SUAN’S REMARKABLE JOURNEY

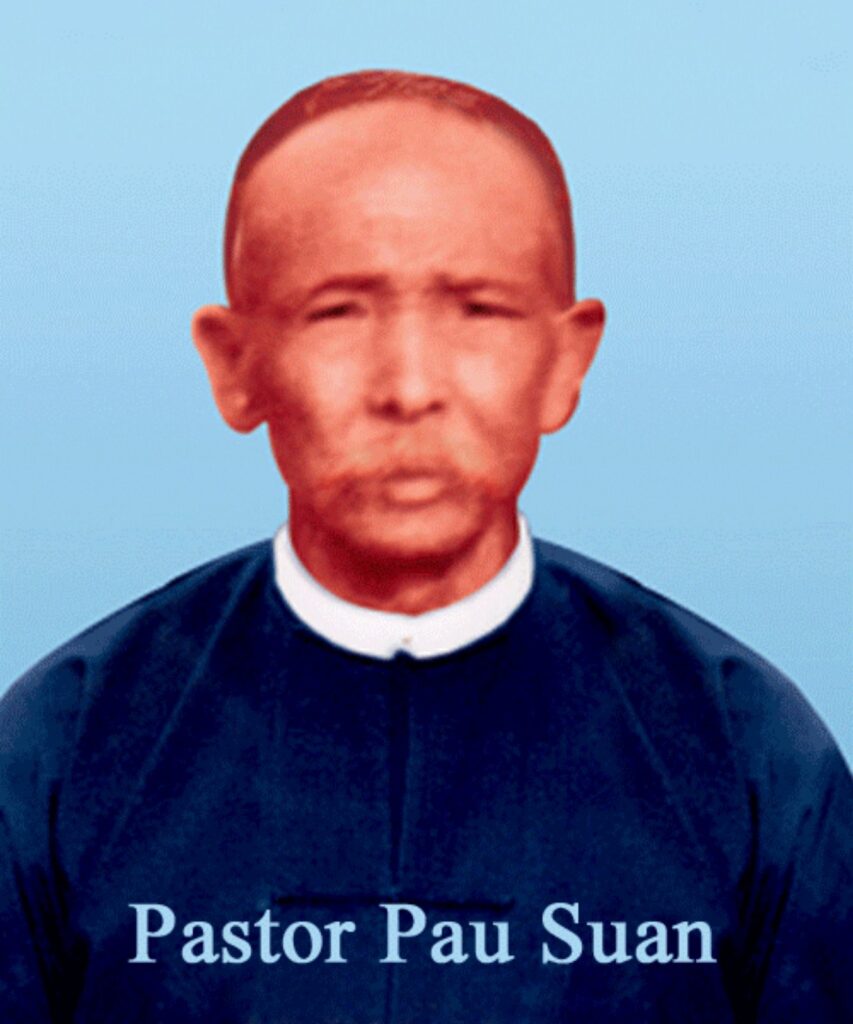

The First Christian Convert in the Chin Hills

And a Visionary Community Reformer

By Kenneth Htang Suanzanang

Birth of Pu Pau Suan

Pu Pau Suan (G. 74-20) was born in February 1875 in Khuasak, Fort White, Chin Hills, Burma (now Myanmar). His parents were Pu Do Thang (G. 74-19) and Pi Vum Vung (G. 141-21), the daughter of Pu Thuam Khup, and the sister of Chief Pau Khai of Khiap Thuam Bawng, who served as the chief of the Buanman clan under British appointment.

Pu Pau Suan’s birth coincided with a significant historical event—the retaliatory attack on Mualbem by the 2,400-strong army of the Rajah of Manipur, which occurred in the same month. 1

Genealogy of Pu Pau Suan

Pu Pau Suan was the son of Pu Do Thang, whose parents were Pu Mang Pau (G. 74-18) and Pi Lam Vung (G. 143-19). Pi Lam Vung, the daughter of Chief Han Kam (G. 143-18), of Mang Thuam Bawng, was from the Kim Lai clan, whose leadership marked its zenith. She was also the aunt of Chief Lian Kam (G. 143-20), chief of the Buanman clan and primary leader of the Siallum Battle, who sacrificed his life for his people and country.

Pu Mang Pau was the son of Pu Tuah Thang (G. 74-17), and Pi Awi Hau (167-18), the daughter of Pu Vum Kam of Zeal Vum Bawng, a descendant of Seal Mang Tuu of Lim Khai Suanh, Vang Lok Khang. Pu Tuah Thang was the son of Pu Lu Mang (G. 74-16). The name of Pu Tuah Thang’s mother and beyond, there are no records that exist about women’s generations.”

Pu Lu Mang was the son of Pu Khan Vum (G.74-15), who was the son of Pu Mat Kim (G. 74-14), the son of Pu Kun Tong (G. 74-13), the son of Pu That Lang (G. 74-12), the founder of Khuasak village. Pu That Lang was a fourth-generation descendant of Pu Thuan Tak, later known as Pu Suantak by some of his descendants who adopted different dialects. Pu Thuan Tak was an eighth-generation descendant of Pu Zo (G. vi – 1), the great forefather of all Chin (Zo) people in Chin State.

Pu Kun Tong, the Sole Heir

Pu That Lang had four sons: Pu Tong Seal, Pu Khum Thang, Pu Kun Tong, and Pu Khup Thang. Pu Kun Tong, the youngest son from the first marriage, became the sole heir of Pu That Lang according to Siyin-Chin tradition, as Pu Khup Thang, born of a second marriage, was not entitled.

Division of Family Lineages/Bawng

Pu Mat Kim had three sons: Pu Tuan Thang, Pu Han Thuam, and Pu Khan Vum. Their descendants are known as “Tuan Thangte,” “Han Thuamte,” and “Khan Vumte,” respectively. However, as female genealogies are not traditionally recognized in the lineage system, the line of Pu Han Thuam concludes with the sixth generation:

- Pi Vung Khaw Dim (G. 69-21), married to Pu Thang Kim (G. 101-21).

- Pi Ngiak Khaw Vung (G. 69-21), married to Pu Vum Khaw Thang (G. 75-21).

The suffix “te” is commonly used to denote a group of people, such as a tribe, race, clan, family lineage, or the inhabitants of a village. Examples include Sizangte, Khuasakte, Thuklaite, Kuntongte and Nguazaangte. Additionally, “te” functions as a plural marker, akin to “s” in English.

Pu Khan Vum had Three Sons

Pu Khan Vum had three sons: Pu Mat Tuang, Pu Lu Mang, and Pu Sawn Mang. Their descendants are known as “Nisa-te” and “Ngalphuakte” for Pu Mat Tuang, “Nguazaangte” for Pu Lu Mang, and “Nguanuai-te” for Pu Sawn Mang, the sole heir of Pu Kun Tong.

Pu Pau Suan had six siblings

They were: Pu Pau Khaw Thang, Pu Khup Vungh, Pu Mang Ngin, Pi Neam Cing (sister), Pu Kam Mang (who passed away on April 2, 1957), and Pu Vungh Kam.

Of the seven siblings, only Pu Pau Suan had descendants. Pu Kam Mang was briefly married to Pi Suan Cing (G. 65-21), but they had no children. The remaining siblings passed away before they could marry.

Pu Pau Suan often remarked that had Pu Vungh Kam lived, he would have surpassed even himself—a great loss to the world. 2

As a Teen

As a 14-year-old during the British annexation of the Chin Hills in 1889, Pu Pau Suan acted as a spy, tracking enemy movements and assisting in setting logs and rocks on hillsides. When released, these crushed the advancing enemy below. 3

Social Reforms of Pu Pau Suan

- Marital Reformer

A Taboo

For twelve generations, endogamous marriage (phuungkhawm) was taboo in Siyin-Chin villages. Although this taboo forbade phuungkhawm, love could not be suppressed, leading to depopulation through abortions and infanticides. Consequently, the Siyin-Chin people are fewer in number compared to other groups.

Courtship

In his early twenties, Pu Pau Suan (G. 74-20) fell in love with his fifth cousin, Kham Ciang (G. 70-20), the daughter of Pu Zong Tuang and Pi Ngiak Mang. Their shared lineage traced back to Pu Khan Vum, grandson of Pu Kun Tong. Pu Pau Suan belonged to the Pu Lu Mang sub-family lineage (Nguazaangte), while Pi Kham Ciang traced her ancestry to the Pu Mat Tuang sub-family lineage (Nisate). Despite cultural taboos, their love endured, and Pi Kham Ciang eventually became pregnant.

Defying Tradition for Love

Pu Pau Suan requested the village priest, a relative, to officiate their marriage. However, the priest refused, bound by the longstanding taboo. Not knowing what to do or where to turn, whether north or south, Pau Suan composed a Chin lyric that goes:

“Ka tungciang a, khaimuuu laam vadial awng e,

Phuung taw tua khua na mu le, tong-hil ka ve,

Phuung taw tua tu, ngil-thang va-aal saan leang e,

Killam zawl a, sawm-sial sai bang ban leang e.”

Tranlation:

“O eagle soaring majestically and free,

Glide gracefully above and search for me.

Find a land where love can stay,

Where customs will not bar our way.

A place where vows are bound with grace,

And destiny is read in fowl’s embrace.

Where wedding feasts with joy resound,

And mithun’s beef is richly found.”

Undeterred, Pu Pau Suan ventured into the wilderness, trapping doves and pigeons. He caught a pair of each and placed them in two cages at the entrance of his house.

Becoming His Own Priest

On October 1, 1900, Pu Pau Suan called Pi Kham Ciang from her father’s house to join him. At the threshold of his home, he assumed the role of priest, spraying mild rice beer—zu phi—from his mouth over two pairs of doves and pigeons while chanting blessings. He invoked prosperity and fruitfulness, marking a pivotal moment of new beginnings in their lives.

The Chant in Siyin-Chin

“Va-khuu awng, Hu-hee awng,

No zong unau kiteang-a,

Sim thing tung-a, Zo thing tung-a,

Tanu toai thei, Tapa toai thei,

Cidam thei, mul-maam thei

Na hi uh ciang,

No nung hong zui tu khu hi.”

“Va-khuu awng, Hu-hee awng,

Tanu na toai thiam vun,

Tapa na toai thiam vun!

Na khua, na tui, cidam-in na zuan ta vun!”

Translation

“O doves, O pigeons,

Siblings, brother and sister,

Born of the same gentle parents,

You brought forth sons and daughters,

In the trees of Sim valleys,

And the Zo hills of leafy embrace,

Healthy and joyful in your flight.

We, too, shall follow your way,

Seeking life and love as one,

Together beneath the sky’s watchful eye.

O doves, O pigeons,

May the Lord bless us as He blesses you,

With sons and daughters of our own.

Grant us fruitful lives,

With health and joy in abundance,

And many sons and daughters to carry forth your blessings.

Now, return to your abode,

To the place where you were born,

As we embark on a new journey,

Hoping for blessings to abound in our lives.” 4

Founding of PhuungkhawmPu Pau Suan and Pi Kham Ciang founded Phuungkhawm, a tradition of endogamous marriage that emerged by circumventing a longstanding taboo established during the time of Pu Thuan Tak, twelve generations earlier. Within a week, five more couples followed suit. Reflecting on this, Pu Pau Suan composed the following lyric:

Phung taw tua-tu Zaangsi lai a,

Pupa’n ngam bang tang ta ze;

Vaimang taw tongdam ciam ing e,

Zaangsi tuanglam tam sak nge.

Translation

“To marry one from the same village of Siyin kin,

Our forefathers forbade, like land deemed forbidden to till or dwell within.

Yet I gained permission through British might,

Clearing the path through Siyin’s land, making it smooth and bright.

While marriage from other villages is allowed,

I sought the heart of one from the same village of Siyin kin and am proud.” 5

Post-Marriage Challenges

Pu Pau Suan and Pi Kham Ciang, guided by their faith in God, courageously opposed the longstanding taboo to safeguard lives and uphold the fundamental right to marry.

After the birth of their first son, Rev. Lian Zam, on December 7, 1900, their refusal to surrender him to community demands placed their lives in jeopardy. Pu Pau Suan’s appeal to Township Administrator Mr. Beckman and District Commissioner Mr. E. O. Fowler resulted in the legalization of phuungkhawm.

To celebrate, Pu Pau Suan donated 300 silver rupees and a bull to the village chief for a feast honoring the British edict that legalized phuungkhawm and prohibited abortion and infanticide under Indian Penal Code 312.

Despite being regarded as a hero by the majority, Pu Pau Suan faced criticism from a conservative minority. 6

The Legacy of Phuungkhawm

With the authorization of phuungkhawm, the taboo was lifted, bringing an end to practices like abortion and infanticide. This transformative reform not only saved countless lives but also laid the foundation for the acceptance of Christianity within the community.

Without phuungkhawm, influential figures from the Siyin-Chins such as Major General Tuang Za Khai, Major Shwang Howe, Pu E. Pau Za Kam, Major Lua Cin, Major Dr. Mang Za Htang, Subedar Vum Tual, Lt. Col. E.K. Kim Ngin, Pu Tual Kam, Lt. Col. Khai Mun Mang, Lt. Col. Dr. Suang Za Pau (Professor), and Professor Dr. Suantak von Kamcindal might never have been born.

On a global scale, if abortion had been legalized universally, transformative figures like Albert Einstein and Thomas Edison might have been lost, depriving the world of their remarkable contributions

Children of Pu Pau Suan

Pu Pau Suan had six children. His first five were: Rev. Lian Zam (December 7, 1900 – December 1, 1940), Pu Tuang Khaw Hau (c. 1902), Pu Thang Khaw Kam (c. 1904), Pi Vung Khaw Cing (daughter, c. 1906), and Saya Vai Khaw Thang (c. 1908 to June 26, 1953). From his second marriage to Pi Son Khaw Dim, he had a son, Dr. Vum Za Lian (D. Mn.), born on November 30, 1945.

Except for Rev. Lian Zam, Saya Vai Khaw Thang, and Dr. Vum Za Lian (D. Mn.), the others passed away before marriage and had no descendants.

Wife’s Death

The love between Pu Pau Suan and Pi Kham Ciang was truly extraordinary—icons of enduring love, inspiring others with their steadfast commitment and unity. As the wisest King Solomon describes, “Love is as strong as death, its jealousy unyielding as the grave” (Song of Solomon 8:6).

“Many waters cannot quench love,

Nor can the floods drown it.

If a man would give for love

All the wealth of his house,

It would be utterly despised.” (SS 8:7 NKJV)

Nothing could extinguish their love—not taboos, traditions, or threats. Fearless and deeply devoted, the couple defied societal conventions and were married on October 1, 1900. However, their love story was not destined to last forever. The death of his beloved spouse on June 22, 1937, brought an end to their time together on Earth. Pu Pau Suan sang these two laments for his beloved wife:

- “Maa bang patpui sen ka ngual koai, Thal bang khomla thong ing e;

Vonmin lawpui koai-neam awng e, Tum bang huai pui nuam ing e.”

Translation:

“My love from our youth, my better half with whom life’s journey began,

Like a broken bow, it endures no longer, and I long for what was.

Through the name of our noble son, we are known,

My gentle spouse, how deeply I wish we could grow old together.”

- Ngai tam sialpui tiin lia-nu awng, Nau bang hong op thiam ve te;

Sang dei tutna saumang zilza, min seal om lai tum dang kom-a,

Phung sau khau bang kawn ing e.”

Translation:

“My beloved, with whom I share the joys of life and love,

You offer me the tenderest care of a loving mother to her child.

Our home, vast and filled with memories,

Was once alive with joy when I returned from hunting with my prey.

But now, with our noble son’s strange illness,

After your passing, we have been forced to move from house to house.”

Remarriage

On May 9, 1938, Pu Pau Suan remarried Pi Son Khaw Dim (G. 64-21). The celebration commenced with the Mopuii Ceremony, a traditional feast hosted at the bride’s home by her father, Jamadar Tun Zam. The following day, May 10, the Ak-ngaw-tanh Ceremony took place at the groom’s house, where the holy matrimony was solemnized by Rev. Thuam Hang. Over the course of two days, the groom provided food and drinks for all attendees.

When Pu Pau Suan passed away on March 3, 1951, their only son, later known as Dr. Vum Za Lian (D. Min.), was barely five years old, having been born on November 30, 1945. He was raised by his widowed mother, Pi Son Khaw Dim, who remained a pillar of support until her passing on March 3, 1991, after living to see five grandchildren.

Dr. Lian (G. 74-21) married Pi Awi Cing (G. 143-23), daughter of Pu Kam Tual (G. 143-22), and Pi Cingh Vung (G. 171-21). Pu Kam Tual was named after his grandfather, Chief Lian Kam, the leader of Siallum Battle who paid his life for his land and people.

- Cultural Reformer

High Bride Prices

After becoming a Christian leader, Pu Pau Suan rejected traditional practices such as demanding bride prices known as mo-man and the expectation that the groom would cover all wedding expenses. This practice left many young men unable to marry, and those who did marry often fell into debt, losing their homes and lands to moneylenders. Since his conversion, Pu Pau Suan actively discouraged Christians from demanding a mo-man. This stance was officially reaffirmed by the leaders of Siyin Churches as follows:

Reformation Adopted

Some viewed the reforms initiated by Pu Pau Suan as extreme. However, on October 3, 1930, the churches in the Siyin Valley held a meeting to reaffirm these changes, drawing inspiration from Paul’s message to the church in Rome:

“And do not be conformed to this world, but be transformed by the renewing of your mind” (Romans 12:2, NKJV).

Christians are discouraged from engaging in the following practices:

- Killing animals to entertain those who come to pray for a sick person of a family.

- If a relative provides an animal for another relative’s funeral known as sathiang-ngaw, the first relative will expect to be returned when they have a funeral.

- Paying the neck of an animal known as sa-ngawng-puak to the wife’s family in a household.

- Demanding a bride-price – mo-man.

Any Christian found engaging in the following actions will face disfellowship:

- Working on Sunday for personal benefit.

- Using opium for personal use or selling it for business.

- Participating in non-Christian feasts. 7

Overcoming Traditions

Burdensome Funeral Practices

In the past, the deceased were not buried immediately but were preserved with fire and kept at home. The funeral process involved three distinct ceremonies:

- Thi-mai – The initial funeral ceremony, held upon the death of a family member.

- Thi-ngin – A secondary funeral ceremony, held at a convenient time, with no set schedule.

- Thi-vui – The final funeral ceremony, marking the conclusion of the process.

Each ceremony typically lasted about three days and included feasting, drinking zu, dancing, and sharing meat and rice.

Long Delay Funerals

Due to poverty, some families could not afford to complete even one funeral rite, sometimes waiting up to ten years before burying their loved ones. In many cases, several deceased family members were buried together after long delays.

Other Burdensome Feasts

In addition to traditional funerals and marriage customs, other feasts placed a heavy burden on the people:

- Ngal-ai – A feast for victory over enemies.

- Sa-ai – A feast held on the occasion of acquiring big game (sa-mang) such as a tiger, elephant, or bison.

- Tong – The grandest and longest feast, celebrating life’s success and wealth.

Christianity liberated them from these burdensome traditions.

Pu Pau Suan’s Early Reforms

Upon overcoming these burdensome traditions, Pu Pau Suan composed the following lyric in Siyin-Chin:

“Sen-a pupa’n sang-le-lal taw,

Zaangsi thimkhua zingsak ze;

Khan a maa bang ka pat ciang a,

Khua vannuai a taang nam maw?”

Translation:

“My ancestors of ancient days,

Made Siyin land in darkness stay;

Their deeds have cast a shadow deep,

Does heaven hear the cries they weep?

When I begin this path of mine,

Does light break through, beyond the line,

And reach across the whole wide land?

Can its glow spread where shadows stand?” 8

Prohibitor of Lamtak – Sa-ngaw

Some Christians desired to continue the traditional practice of slaughtering numerous animals for funerals known as Lamtak – Sa-ngaw, but Pu Pau Suan, through his example, taught them to abandon this custom, although very few followed him. His daughter-in-law, Pi Dim Lian, composed a lyric in this context:

“Zua hawm thiam le ka tin min ngei,

Thian tong na san thangbel ze

Tha na kiak ni, ai-sa na nial,

Khua-zalai-a thang sa’ng e.”

Translation:

“My father-in-law, both wise and kind,

And brother-in-law, with truth and wisdom aligned,

Your faith in God’s word brightly shines,

Renouncing the slaughter, in countless towns, you draw the lines.”

Legacy of the Prohibition of Lamtak – Sa-ngaw

Although most did not follow Pu Pau Suan’s example of avoiding the butchering of many animals at funerals, known as Lamtak – Sa-ngaw, his stance alleviated the financial burden on impoverished families. Some argued, however, that since Pu Pau Suan owned many cattle, following his lead would only expose their poverty. His son, Rev. Lian Zam, upheld this principle, and its strict observance has been in effect since his death, as it was his final wish.

At Pu Pau Suan’s passing on March 3, 1951, mourners traveled from Kalaymyo to honor him at his funeral on March 5. However, two young men headed in the opposite direction. When questioned about avoiding the funeral of such a revered leader, they replied, ‘Even dogs wouldn’t waste their time there,’ referencing the absence of Lamtak – sa-ngaw, a testament to Pu Pau Suan’s enduring legacy. 9

3. Agricultural Reformer – Transition to Advanced Agriculture

Pu Pau Suan pioneered the transition from primitive hillside farming, also known as swidden (slash-and-burn agriculture), to more advanced practices such as horticulture and husbandry. Although his methods were not widely embraced at first, his influence became evident through the exceptional crops cultivated by the writer’s parents, Saya Vai Ko Htang and Pi Dim Lian, who were the hardworking sole breadwinners for Pu Pau Suan’s large family.

They cultivated coffee and a variety of crops, including cabbages, cauliflowers, oranges and citrus fruits, while also producing milk, butter, and a distinctive variety of sugar cane celebrated for its exceptional flavors. Their cane sugar production stood out with three notable varieties: Tuu-pui, large sugar cane, Tuu-ngo, prized for its rich flavor, and Phaai-tuu, a unique variety originating from Manipur. The sugar cane juice, in particular, was extraordinary and unforgettable for its exceptional quality.

In this regard, Pu Pau Suan composed the following lyrics in appreciation of his daughter-in-law, Pi Dim Lian, the mother of the writer:

- “Taang ka toai lia ka toai awng e, Pham tu bek-a hing ing e;

Vonsen ngualkoai lia khat tangh awng, Nun thum taw kim in te nge.”

Translation:

“My children, both daughters and sons, so dear,

Born to pass from this world, as is clear;

The cherished wife of my younger heir,

A lone-born daughter, beyond compare.

I liken you to my mother’s sweet milk,

Pure and precious, smooth as silk.

Your life’s a blessing, tender and bright,

A beacon of love, a radiant light.”

- “Lia khat tangh hanlung ciam ve tia, Tul dei tu bang suan ve tia.

Ka kiak nu a kot kawl zing vai, Vonkoai mun muang zo ing e.”

Translation:

“You, a lone-born daughter, so strong and true,

Through trials and struggles, your best you drew.

You planted success with care and grace,

A legacy bright in its rightful place.

Content I am, as I near my rest,

Knowing my home will be in your best.

With hands so steady and heart so pure,

You’ll keep it in order, that’s for sure.”

Legacy of Advanced Agriculture

Initially met with resistance, the transition to advanced agriculture eventually became a vital source of income for the people of the Siyin Valley. Over the decades, the region transformed into a hub for modern farming practices. Oranges from Thuklai and Pumva reached the market, but they paled in comparison to the exceptional quality of Pu Pau Suan’s oranges—renowned for their thinner skin, juicier texture, and sweeter taste. These attributes were made possible by an ample supply of water from two natural springs.

Premium oranges and apples from the region, often referred to as ‘Chin oranges’ or ‘Chin apples,’ gained recognition in the Mandalay and Yangon markets. The introduction of apples to the region is credited to Pu Thang Tun of Limkhai, who pioneered the cultivation of Leidaw apples. His initiative was later embraced by other villages, contributing significantly to the region’s economy and agricultural reputation. 10

- Educational Reformer

Chin Chiefs’ Early Education

There were no schools in the Chin Hills before 1904. However, Dr. East noted, “The two men, Pau Suan and Thuam Hang, being chiefs must have had some education, for they were able to write in Burmese.” This highlights the importance of education in the region, which likely influenced their request for a school to further enhance educational opportunities for their community. In this context, Pu Pau Suan composed a lyric as it goes:

“Kil bang khan-a, len-nguallai pan,

Vai tong cian tel masa nge;

Pupa thei-lo za-lun Thianmang,

Kiakmawk tuanglam sial ing e.”

Translation:

“Among my friends, I stand alone,

First to learn the script and tongue,

Of Burmese language, deep and wide,

A gift I claim with humble pride.”

“The faith of lords, so strong, so bright,

My ancestors knew not its light.

Yet now I’ve learned, and by God’s grace,

I build the path to endless days.” 11

Chiefs’ School Request

While Dr. East acknowledged Pu Pau Suan and Pu Thuam Hang as chiefs requesting a teacher, it was the appointed chief, Pu Khup Pau, who held the authority to make commitments. He promised to send 30 boys from Khuasak, 30 from nearby villages, and to construct a school, a teacher’s house, and a dormitory for distant students.

During this visit, Dr. East, a medical doctor, is believed to have influenced both Pu Pau Suan and Pu Thuam Hang to embrace Christianity. 12

On March 31, 1904, the American Baptist Mission (ABM) leaders, Rev. Carson and Dr. East, sent Saya Shwe Zan, a dedicated missionary-teacher, to Khuasak. The school in Khuasak was opened in April, 1904. In July there were 20 pupils at Khuasak School. The highest level of education offered was the 7th Standard, and those who completed the 3rd Standard were able to read, write, and speak Burmese.

The First Operated School in the Chin Hills

While other schools in Hakha and Tiddim had been closed, Pu Pau Suan made a bold request for a school in Khuasak, promising 60 students—30 from Khuasak and 30 from surrounding villages. The school opened immediately after Saya Shwe Zan’s arrival in April 1904. Although the materials for the school and hostel buildings were already on site, construction had not yet begun. Dr. East, frustrated by the delay, instructed Saya Shwe Zan to return to Hakha. However, the dedicated teacher, displaying remarkable resilience, responded, “I will try my best. I have operated the school in my humble house, which has already been completed.”

The True Sacrifice and Commitment of Rev. Shwe Zan

The legacy of Khuasak School will always be tied to Rev. Shwe Zan’s unwavering dedication, self-sacrifice, and resilience. In the early 1900s, the Chin people were largely uneducated and isolated. Rev. Shwe Zan, originally from Henzada, the fertile heart of the Irrawaddy Delta region in Burma, was a man of deep conviction. His decision to leave behind a life of comfort for the harsh conditions of Khuasak was like a fish being taken from water and placed in a desert. This profound commitment marked the beginning of a new chapter in both education and Christianity in the Chin Hills. 13

Legacy of Khuasak School

Khuasak School initially offered education only up to 7th Standard in Burmese. However, before and after World War II, a private high school was established, later relocated to Thuklai and upgraded to a State High School in 1947. This made the Siyin Valley the birthplace of the region’s first educated individuals. Today, this pioneering legacy is evident in the 1,143 secular degree and diploma holders, including Ph.D. recipients, and 422 religious degree holders, including those with doctorates, who trace their roots to this foundational institution.

The school also produced 239 gazetted officers, among them notable figures such as Pu Albert Lun Pum, the only Union Minister from Chin State, and Pu Tuang Za Khai, the only Major General from Myanmar’s seven ethnic states. Additionally, Pu Vum Ko Hau served as an ambassador. Four Siyin-Chins were honored with Myanmar’s highest political award, the Naing-gant-gon-yi.

Following the 1962 military takeover, three of the five highest administrators appointed to Chin State were Siyin-Chins: Lt. Col. E.K. Kim Ngin, who later became head of the Regional Party; Lt. Col. Khai Mun Mang; and Col. Son Ko Vum. The Siyin-Chin community also excelled in the medical field, with four of its members—Dr. Ngin Thawng, Dr. Kam Za Dal, Dr. Cope Za Pome, and Dr. Suantak von Kamcindal—holding the position of Director of Health, the highest rank in Chin State’s Department of Health.

Among the 23 heads of departments in Chin State, 13 were Siyin-Chins, further demonstrating the lasting impact of Khuasak School on the region’s leadership and development. 14

- Religious Reformer

Edited Excerpt of Shwe Zan’s Letter to Dr. East (July 25, 1904)

Sir:

“We, the three of us in the missionary family, are very glad. From the time we arrived in Koset (Khuasak) until now, we have been preaching as best we can. One man, named Paung Shwin (Pau Suan), one of the three chiefs you met, now believes that Jesus can save him from his sins and give him life. He has given up all his bad ways and comes to worship with us regularly, along with his wife and mother. He is very earnest in preaching to others. Some men have tried to scare him by speaking against his faith, but he does not care what they say. The more he learns about Christ, the more he preaches to others. When you come to Khuasak, he will be baptized immediately. Please come soon, if possible.”

“One man named Tum Harm (Thuam Hang), who is chief among the three chiefs, has now begun to believe in Jesus. Tonight, he came to me for prayer. Dear master, please remember Thuam Hang in your prayers. Oh, my dear master, if you were here now, you would be so glad for Christ’s work. Please also remember Pau Suan and his household in your prayers. I have tried my best to write in English. Please understand my meaning as well as you can.”

Your obedient servant,

Shwe Zan 15

Pu Pau Suan: The Sole First Christian Convert

In early 1904, Pu Pau Suan, together with other chiefs, requested a teacher from Dr. East in Hakha, with the intent of establishing a school in Khuasak. Upon the arrival of Shwe Zan and his family, Pu Pau Suan and his wife, Pi Kham Ciang, along with their mother, Pi Vum Vung, and their infant son, Lian Zam regularly attended worship with the Shwe Zan family. 16 On July 10, 1904, they accepted Jesus Christ as their personal Savior and publicly professed their faith as Christians. 17

Pu Pau Suan’s lyrics, the Memorial Monument he erected, and a letter from Shwe Zan to Dr. East on July 25, 1904, confirm that no one in the region had converted to Christianity before him. Even Rev. Thuam Hang never disputed Pu Pau Suan’s claim as the Sole First Convert. Why, then, should we debate this 120 years later, in 2024?

“Thianmang tongdam za ih lai pan,

A sang masa kei hi’ng e;

Lei bang hong leal hau ka ngual ten,

Sai bang hong sawm thiam sa’ng e.”

Translation:

“Among countless hundreds, I stood alone,

The first to accept God’s truth, my own.

Those of my age turned against me,

Hunted like elephants, relentlessly.” 18

Unready for Baptism

In mid-October 1904, Dr. East toured the northern region, visiting Tiddim and the Siyin area, where he intended to baptize the converts at Khuasak. However, in a letter to the mission office in Boston, USA, he explained that he had decided to postpone their baptism to allow for further instruction.

Dr. East expressed confidence in their conversion, commending their faithfulness and zeal in preaching Christ. He noted that they had even built a stone baptistry near a spring in anticipation of the event. Dr. East shared his hope to baptize them during his next visit and described the work among the Siyins as the most promising. (Letter dated December 31, 1904). 19

Pu Pau Suan’s Conversion Story

“Unfortunately, little is recorded about the events leading up to the conversion of Pau Suan and his wife,” stated Revd Dr. Robert G. Johnson. 20

Despite this, the legendary reformer faced widespread rejection, treated like a leper for his beliefs. This alienation drove Pu Pau Suan to invite a teacher into his life and cling to him upon his arrival, seeking not only a better way of life but also eternal life. His motto, “The light shines in the darkness,” reflected his perception of traditional religion (Lawki) as darkness and Christianity as the light (Jn 1:5, NKJV).

Pu Pau Suan believed that Lawki religion imposed labor and heavy burdens, contrasting it with his favorite Bible verse: “Come to Me, all you who labor and are heavy laden, and I will give you rest” (Mt 11:28, NKJV). While many pastors sought out Pu Thuam Hang, Pu Pau Suan actively searched for pastors who could guide him toward a better way of life.

To fully grasp how Pu Pau Suan became a Christian, one must first understand his role as a social reformer. His journey is encapsulated in the following lyric:

“Pupa puaklel zinleang za-tam,

Khan-a sum bang nial ing e;

Hong leal lo aw, hau ka ngual awng,

Thaang-vui si bang theau sak nge.”

Translations:

“The burdens my forefathers could not withstand,

Bound to devils in countless lands,

In my life, I stood to fight,

Against the storms that raged with might.

Mock me not, men of my day,

For I quelled the winds at Thaangvui’s bay,

Where endless gusts once held their sway.”

The writer believes why little is recorded about the events leading up to the conversion of Pau Suan and his wife because they were converted by Saya Shwe Zan, who left no record except his letter to Dr. East dated July 25, 1904. In contrast, Dr. East, who was directly involved in Thuam Hang’s conversion alongside Saya Shwe Zan, left us the Burma Manuscript, which was later published in book form. However, some of its contents may be biased. 21

Pu Thuam Hang’s Conversion Story

According to a letter from Shwe Zan, dated July 25, 1904, Pu Thuam Hang began to believe in Jesus. However, by mid-October, during Dr. East’s visit to Khuasak, he was still struggling with nat worship. The community believed that touching the skull of a sacrificed animal would result in death. Saya Shwe Zan explained that this sacrificial system was the work of the devil and urged Pu Thuam Hang to break free from all works of darkness in order to receive God’s blessings.

Guided by Saya Shwe Zan, Pu Thuam Hang spent days in deep contemplation, learning to pray to the God who created heaven and earth. In a pivotal moment, he took a stone and struck every skull, then sat down, ready to die. When death did not come, he proclaimed: “You are a lie; I will worship the God of heaven.” Saya Shwe Zan supported him throughout this struggle and rejoiced in his decision to embrace Christianity.

Pu Thuam Hang’s son, who had been suffering from tuberculosis, recovered and lived for many years. According to the Burma Manuscript, dated November 19, 1904, and recorded by Reverend Dr. East, this event may explain why Dr. East postponed the baptism from mid-October to May 11, 1905. 22

The First Baptisms in Chin Hills

The first baptisms in the Northern Chin Hills took place at a stream named Ak-awm Lui near Khuasak, in the Siyin Valley, close to Fort White in the Tiddim Subdivision.

On May 11, 1905, Dr. East baptized the following individuals:

- Pu Pau Suan and his wife, Pi Kham Ciang

- Pu Thuam Hang and his wife, Pi Dim Khaw Cing. 23

Persecution of Pu Pau Suan

Pu Pau Suan endured several acts of persecution.

First, he was forbidden from living within the village boundary, which was reserved for the Annual Tualbawl Ceremony. As a result, he was forced to reside outside the village in an area called Khuakhuan.

On April 10, 1925, his house was burned down, destroying a large stockpile of timber stored beneath it—enough to build a new home—as well as firewood that had been stocked in the woods for cooking and warmth.

In addition, his water supply was defiled with pig dung. Pu Pau Suan and his family were excluded from relatives’ feasts due to their refusal to drink zu (traditional fermented drink).

During one such feast, when a cow was killed, a shot was fired at its forehead, seemingly aimed at Pu Pau Suan himself. 24

CAREER IN MINISTRY

Early Ministry

Pu Pau Suan was elected as a deacon when Khuasak Church was organized on February 17, 1906. He attended preacher training from June 1 to August 31, 1906, and began his active ministry on September 1. His initial evangelistic efforts were focused on the Siyin Valley and Sukte Gungal area within the Tiddim Subdivision. Occasionally, his missionary tours extended to Bualkhua in the Ngawn area and Lumbang in the Zanniat area within the Falam Subdivision. In 1911, he pioneered the mission in Thangnuai, becoming the pastor there, and expanded his outreach into the Khuano areas.

Inspiring Motivator

Pu Pau Suan was a natural motivator. When he introduced endogamous marriage, five couples embraced the practice within a week. Among them was Pu Huat Kam (G. 59-20), a brother of early convert Pu Thuam Hang. Though in love with Pi Suang Cing (G. 73-20), Pu Huat Kam had hesitated to marry—until Pu Pau Suan’s example inspired him.

While preparing to clear a swidden by felling large trees, Pu Pau Suan devised a plan to encourage his friends to marry. Following the Chin custom of reciprocal labor, he invited five friends, including Pu Huat Kam, to volunteer in the work, knowing he would later repay their help when needed. As the host, he brought lunch for all, including zuthiang (rice beer). Pretending to be drunk, he spoke boldly, saying what he had previously hesitated to express. His tactic worked—moved by his words and example, the five couples soon married, embracing endogamous marriage just as Pu Pau Suan and Pi Kham Ciang had done.

Sharing the Faith

Upon discovering Jesus, the Messiah, Andrew called his brother Simon Peter, just as Philip reached out to his friend Nathanael (Jn 1:40–51). Similarly, Pu Pau Suan must have informed his cousin, Pu Thuam Hang, about his newfound faith. As the first convert, Pu Pau Suan likely played a key role in assisting Saya Shwe Zan in converting Pu Thuam Hang and may have inspired the seven others, including Pu Lam Suan, who were baptized on February 1, 1906. His influence also extended to Pu Hang Suan, the first convert from Thangnuai village, who was baptized on May 12, 1906. 25

Soul Winning in Voklaak

Accompanied by the first converts, Pu Pau Suan and Pu Thuam Hang, Rev. Shwe Zan from Khuasak came to Voklaak to conduct a series of evangelistic meetings. On November 18, 1909, Pu Kam Cin, Pu Thang Sawm, Pu Thuam Khai, Pu Pau Thual, and Pu Awn Kim were converted to Christianity. However, they reverted to their old traditional religion.

Conversion of Pu Lam Suan

Despite the earlier reversion of other converts, Pu Lam Suan, who had been suffering from a prolonged illness, sought help from the missionaries in Khuasak. In response, Saya Shwe Zan, Saya Pau Suan, and Saya Thuam Hang visited Voklaak, leading Lam Suan and his family to convert to Christianity on January 10, 1910. Pu Thang Lian, a leader of the Laipian Movement, repeatedly tempted Lam Suan to drink zu and return to Laipian, but his efforts were unsuccessful.

Pu Lam Suan, Faithful Until His Passing

Following the Fourth Chin Hills Baptist Association (CHBA) Annual Convention held in Khuasak from March 18–20, 1910, Rev. Shwe Zan, Sayas Pau Suan, and Thuam Hang visited the believers in Voklaak. They found that Pu Lam Suan and his family were the only ones who had remained steadfast in their Christian faith. Lam Suan stayed devoted until his passing on January 4, 1934.

Conversion of Pu Zong Kim

Despite challenges, the Baptist Church in Khuasak persisted in holding evangelistic meetings in Voklaak. Nearly a decade later, on December 20, 1920, Pu Zong Kim and his family accepted Christianity and joined the Baptist Church. Their conversion sparked a gradual movement, as others followed, including Pu Kaang Khup, Pu Thang Tuang, Pu En Kam, Pu Hong Thuam, and Pu Kham Hang, along with their families. 26

BBC Convention in Henzada

Pu Pau Suan likely participated in the Burma Baptist Convention (now the Myanmar Baptist Convention) in the early 1910s. His travels took him across Myanmar by ship and train, passing through cities like Monywa, Mandalay, Toungoo, and many others on his way to Henzada via Rangoon. Inspired by this journey, he composed a lyric that reflected his determined spirit and unwavering faith:

“Seino ciang-a mung bang ka tup,

Kaa bang tung la om ngawl ze;

Seino ciang-a ngaikhua ci-teng

Ka duangbaang-khial om ngawl ze.”

Translation:

“Since my childhood, I’ve set my sights,

No goal too high, no distant heights.

Since my youth, with steady pace,

I’ve reached each dream, no goal misplaced.” 27

Inclusive through Love

I recall accompanying my grandfather, Pu Pau Suan, to the home of Pu Awn Khai, brother of Pu Lam Suan, who was baptized as part of the second batch of candidates in 1906. Lam Suan later became a preacher alongside Pu Pau Suan. Pu Pau Suan was invited to participate in mo-anle, a Siyin tradition where newlywed couples visit the bride’s family, bringing fine foods and receiving a similar gift in return. In this custom, mo refers to the bride, an to food, and le to exchange. In an act of respect, Pu Pau Suan was welcomed as the head of their family, embodying inclusivity and love as though he were an immediate family member.

A Lifelong Commitment

In 1928, Pu Pau Suan’s formal ministry came to an end due to deteriorating eyesight and lack of funds, at which point his son took over. Dr. Joseph H. Cope of the American Baptist Mission in Fort White marked this transition on July 24, 1924, with the following statement:

“This is to certify that Lian Zam of Koset (Khuasak) village, Tiddim Sub-division, is a regularly appointed evangelist of the American Baptist Mission. He has served in that capacity since 1922, during which time he worked steadily and caused no trouble. He was appointed to succeed his father, Pau Suan, who worked as an evangelist from 1906 until 1928, when, on account of his eyesight and the lack of funds, he was laid aside and his son took his place.” 28

Though his salary was discontinued, Pu Pau Suan’s dedication to serving his loving God remained steadfast. He continued his ministry as a layman and volunteer, carrying on his work until his passing. 29

Note: The dates may seem confusing; however, they are quoted directly from the original document.

Legacy of Christianity in the Chin Hills

Christianity began in the Chin Hills in 1904 with two pioneering couples: Pu Pau Suan and Pi Kham Ciang, and Pu Thuam Hang and Pi Dim Khaw Cing. They were baptized on May 11, 1905, followed by seven more individuals on February 1, 1906. On February 17, 1906, Khuasak Church was formally organized as the first church in the Chin Hills.

The 1954 Golden Jubilee Celebration

When the Golden Jubilee was celebrated in 1954, Khuasak village was overwhelmed by approximately 5,000 delegates from across the Chin Hills, the Kale-Kabaw Valley, and delegates from Yangon, including Saw Samuel Zan, the firstborn of Rev. Shwe Zan. The crowd was so dense during the night dismissal that movement was difficult, with everyone pressed together and walking on tiptoe.

The 1979 Diamond Jubilee Celebration – Misleading Play

In April 1979, Khuasak hosted the Diamond Jubilee commemorating the 75th anniversary of the first Christian converts. The programs were excellent, featuring 75 cannon salutes and concluding with Handel’s Messiah performed by the Hallelujah 75-voice choir. However, an entertainment skit depicted a missionary speaking Chin with an American accent, asking, “Pau Suan, why do you want to be a Christian?” The actor playing PuPau Suan replied, “Only if I can marry my lover, Kham Ciang,” eliciting laughter. While amusing, this portrayal was misleading—there were no missionaries or Christians in Khuasak when Pu Pau Suan married in 1900, four years before Christianity arrived. Instead, Pu Pau Suan’s phuungkhawm served as a catalyst, paving the way for Christianity.

The 2004 Centennial Celebration

By the Centennial celebration in 2004, it was reported that 10,000 people participated. However, the writer believes the Golden Jubilee in 1954 drew an even larger crowd, as there was only one denomination—the Baptist Church—if the Catholic Church, which existed by then, is not counted.

Post-1954 Developments

After 1954, the Baptist Church began to separate into various denominations and associations. Today, Christianity is nearly universal in Northern Chin State, while Southern Chin State has a small Buddhist minority.

Pu Pau Suan: An Outstanding Figure

Rejoicing with Those Who Rejoice

Pu Pau Suan was a prominent figure in our community. It was said that on November 9, 1944, he led the singing during the V-Day celebration of the Siyin Independence Army (SIA) after their victory over the Japanese. Beginning at Sakhiang, the captured Japanese base camp, the congregation sang, “Miza suilung atai bel ni Nine November, Nineteen Forty-four” – a song commemorating November 9, 1944, as the happiest day for the people. As the procession made its way to Ngallu-mual, Pu Pau Suan chanted the hero’s song (hanla) at every significant point along the route. When they reached Ngallu-mual, the entire community, young and old, came out to join in the celebration, singing and dancing in jubilation. Each time Pu Pau Suan finished a verse of the hanla, the crowd responded with the firing of guns in the air. Just as King David’s wife despised him when he danced before the ark, Pu Pau Suan was criticized by a few for his spirited patriotism. Yet, the majority admired his heartfelt joy during such a historic moment. As Paul says, “Be happy with those who are happy, and weep with those who weep” (Ro 12:15 NLT).

Weeping with Those Who Weep

Pu Pau Suan regarded Saya Suang Khaw Kam, the son of Pu Thuam Hang, as his own son, Rev. Lian Zam. He composed a lyric reflecting on their early demise:

“Maa bang patpui von ngeal awng e,

Phai mitsot etcim la’ng e;

Thiam bang na sin Thian mang thin-thu,

Simlei khanngual sing awng e.”

Translation:

“My two sons, with whom I began this journey,

My eyes never tire of seeing you;

Your deep knowledge of God’s word sets you apart from your peers,

Shining with grace and wisdom.”

When his nephew, Lt. Mang Za Lian and grandson, Lt. Thura Pum Za Kam (MC, military cross), were killed in action, he wept and prayed, ‘God, why should my descendants be annihilated?‘ I can still picture the depth of his sorrow over their loss. I also remember how he mourned when his colleague, Rev. Thuam Hang, passed away on July 7, 1950; he wept deeply at his bedside. Just seven months later, on March 3 of the following year, he himself passed away, joining his friend in rest until their beloved Jesus comes to bring them home for eternity. 30

A Leader in Times of Crisis

Pu Thian Pum once shared a story about a young officer, Subedar Mang Pum of the Chin Hills Battalion. While home on leave, Mang Pum, full of bravado, fired his gun and shouted threats, attempting to intimidate the young, inexperienced Christians, hoping to drive them from their faith. The entire community, gathered at a funeral to comfort a grieving family, heard the gunfire and taunts.

As a wise leader, Pu Pau Suan knew exactly how to respond to such challenges. In a calm, solemn voice, he declared, “How dare the pitiful Mang Pum challenge Christianity, a faith established by the permission of the British government and protected by its laws.” Holding a rope, he added, “I’ll go and catch him and put him in prison.” With that, he left the mourning house.

After some time, he returned and said, “I couldn’t catch him; he’s gone far beyond the Luipi stream.” Though it wasn’t practical to apprehend Mang Pum, Pu Pau Suan’s words instilled confidence in the young Christians. His calm yet authoritative demeanor reassured them of the church’s strength and the leadership’s protection. 31

Psychological Instincts

Pu Pau Suan possessed the instincts of a psychologist. At home, he displayed two guns: one with an extra-large barrel, reserved for himself, and a smaller, more refined one for U Suan Khaw Pau. With a smile, he would often say, “The bigger one is for Suannang, and the smaller one is for Vumpui,” making both of us feel special in his own unique way. 32

With a Bible and a Law Book

During Nehemiah’s time, the builders worked with tools in one hand and weapons in the other (Neh 4:17). Similarly, Pu Pau Suan’s cupboard was filled with Bibles and law books, a symbol of his wisdom and leadership.

Whenever I met Pu Thian Pum, the chief of Buanman, and Wuna Kyaw Htin Major Awn Ngin, they would often say, “God had a wise plan for His church. In nurturing and protecting it, He placed Pu Thuam Hang in the pulpit with a Bible, while Pu Pau Suan stood with both a Bible in one hand and a law book in the other.” They saw this as God’s method of fostering teamwork in the church, a plan that continues today. 33

Easing Tual Restrictions

Pu Pau Suan and his comrades worked tirelessly to ease the burdens of the Annual Tual-bawl Festival, which strictly enforced village boundaries and imposed severe penalties for any trespassing animals. One year, a Christian villager faced this challenge when his prized mithun wandered beyond the boundary. Panicked, he lifted his hands in prayer, desperate for divine help. But in his flustered state, he mistakenly cried, “Pathian Li-li, Sialpui Li-li!”—meaning, “Come on, God; come on, mithun!” instead of his intended prayer, “O God, help me; let my mithun come back.”

The mix-up happened because, in his panic, he used “Li-li,” a phrase the Siyin-Chins used to call mithuns, addressing God and the animal in the same way. This amusing slip showed both the stress caused by the festival’s restrictions and the unintended humor in such moments. After years of struggle, Pu Pau Suan successfully advocated for limiting the Tual boundary to the designated compound rather than the entire village, bringing much-needed relief to villagers and ensuring they wouldn’t need to resort to such frantic and mistaken prayers. 34

Big Game Troubles

Pu Pau Suan, an avid hunter, was deeply passionate about hunting, a livelihood cherished by the Chin people. His enthusiasm led to trouble when the government confiscated his one-barrel gun after he shot two Indian bison outside his licensed zone. Despite having a legitimate license, he regretted the loss of his prized firearm and spent years trying to recover it. Ultimately, he found peace by acquiring two replacements: a percussion-lock firearm and a flintlock gun.

One bison skull was prominently displayed at the right side of his main door, while the other was given to Pu Khai Vum for a mithun festival [sial-ai] celebration. To balance the display, Pu Pau Suan placed a mithun (sial) skull on the left side of his house. His hunting repertoire included not only bison but also bears, boars, deer, barking deer, and mountain goats. Although some companions teased him for being cautious around steep cliffs, Pu Pau Suan would proudly counter, “See how many mountain goats I’ve brought back!”

Relation with Pu Khai Vum

Pu Khai Vum and Pu Pau Suan, both grandsons of Pu Mang Pau, were second cousins who shared a bond as close as that of siblings. Pu Khai Vum, the son of Pu Hau Mang, was a successful businessman who served as Acting Chief of Khuasak, succeeding Chief Lian Thawng until Burma’s Independence on January 4, 1948. Following independence, he was elected headman of Khuasak by majority vote. His son, Pu Suan Khaw Lian, likewise earned distinction as a wise and respected headman of Khuasak for many years. Pu Pau Suan, the son of Pu Do Thang, had a particularly close relationship with Pu Khai Vum, who embraced the role of an elder brother in their enduring bond.

Although Pu Khai Vum never became a Christian, their relationship was deeply profound. As a gesture of their closeness, Pu Khai Vum named his firstborn Suan Khaw Lian, adopting Pu Pau Suan’s surname. Similarly, Pu Pau Suan honored this bond by naming his third granddaughter Ciin Ko Hau after Pi Man Ciin, Pu Khai Vum’s wife. When Pu Pau Suan’s youngest son was born, he named him Dr. Vum Za Lian (D. Mn.), in honor of Pu Khai Vum.

Many years after Pu Khai Vum’s passing, his grandson, Revd Dr. Vum Khat Pau (D. Min.), son of Pu K.T. Ngo Za Lian and Pi Mang Za Cing, rose to prominence as the General Secretary of SRBA and now serves as the Senior Pastor of YSBC. His younger sister, Pastor Lian Dim Mang (L.Th.), volunteered with the Chin Christian in One Century (CCOC) movement of the Zomi Baptist Convention (ZBC) and served as a missionary in four challenging locations in Myanmar from 1986 to 1993. During her mission in Chat, Mindat Township, she built a church. After graduating from MITC, Insein, in 1998, she led a CCOC evangelistic team to Paletwa Township from 1999 to 2001 and built a church in Doe-new-san while serving as a missionary. In 2001, she became Assistant Pastor of Tahan Baptist Church in Kalay, a role she held until her marriage to Thawng Cin Tual, son of Capt. Lian Pau and Pi Nuam Khan Cing in 2004.

Heritage of Family Hunting

My grandpa (Pupu) was the most skilled hunter in our family. He hunted impressive big game known as sa-mang, including two bison (zangsial), bears (vom), and two-horned deer as large as a mid-sized cow (saza). While these were considered big game, the Chins did not classify sazuk, a two-horned deer with antlers split into eight smaller horns, as such. Wild boars (ngalh), bucking deer (sakhi), and mountain goats (sathak) were also not regarded as big game.

Pupu was the model hunter among them, with U Pau, U Vai, and Pano Vumpui following in his footsteps as they, too, pursued bears and wild boars, considered prized big game known as sa-mang. Papi Lian Zam, another remarkable hunter, often quoted Jacob’s words to Isaac, saying to his father (Pupu), “The LORD your God gave me success” (Genesis 27:20). It is said that Papi had visions of the exact locations of his prey, ensuring he never returned home empty-handed.

My father (Papa), Vai Khaw Htang, was an expert trapper, consistently capturing numerous animals with his skill and ingenuity. While Pupu was the model hunter in our family, Pu Pau Suan, another legendary figure in our lineage, also demonstrated remarkable hunting prowess, securing game that further enhanced our family’s reputation.

However, unlike my forebears, I was spared by God for His ministry and have never taken the life of any game. (Pupu means grandfather; Papi, father’s eldest brother; Pano, father’s youngest brother; and “U” is a title used for elder brothers.) 35

Wrestling and Winning a Bear

Once, Pu Pau Suan found himself wrestling a mother bear. With its powerful paws, the bear overpowered him, leaving his skin scraped from his skull. Realizing there was no point in continuing the fight against the ferocious creature, he pretended to be dead. The enraged bear, believing him defeated, stepped back.

As it turned to leave, Pu Pau Suan said, “I’ve reserved one thing for you,” and drew his knife from its sheath. The bear, returning with a roar and baring its full jaws, charged at him again. In a swift motion, Pu Pau Suan thrust his knife directly into the bear’s mouth. The bear let out a thunderous roar and fled into the woods, surrendering the fight to Pu Pau Suan. 36

As a Historian

Pu Pau Suan was a historian who relied on assistants to write in Chin. He dictated the Chin Genealogy (Zo Khangsimna) and Zo History to Pu Lu Khaw Mang and Pu Mang Suan. After Grandpa’s passing, my mother, Pi Dim Lian, inspired the compilation of his manuscripts, which were copied and assembled into handwritten book forms. 37

Never Rich nor Ever Poor

Pu Pau Suan often said, “I am never rich nor ever poor.” One of his compositions reflects this sentiment: “Pha la tang nge, pha la ta’ng. Pazua hen thiam pha la ta’ng,” meaning he could not compete with his forefathers in terms of material possessions. The Siyins owned the largest territory in Chin State, bordering the Sagaing Division, which included land in the winding part of the Letha range. Prominent landowners included Pu Pau Suan, Honorary Capt. Pau Chin (Knabb Commandant), Subedar Za Shuan, Subedar Mang Pum, Jamadar Ngin Vum, Pu Khan Lian (father of Major General Tuang Za Khai and Pu Pau Suan’s brother-in-law), and Chief Khup Lian of Lophei. Grandpa’s name was ranked among these officers and chiefs, holding equal importance.

His territory, known as Tuaizang, was a vast area spanning miles. It was purchased from a Burman with six cows by Pu Lu Mang, the grandfather of Pu Pau Suan. From 1950 to 1952, it was cultivated, producing sugar canes as tall and stout as bamboo due to the excellent soil. It was said that when grandpa’s cattle and ponies were led out in the morning, the herd extended from his house to the village gate – kongpi. This seemed unbelievable to me until I learned it was true, as the cattle were led out from the northern gate of our house then, closer to ‘kongpi.’

Destruction of Pu Pau Suan’s House

On April 10, 1925, Pu Pau Suan’s house was burned down by an anti-Christian, just the night before he was set to leave home to purchase corrugated iron roofing. In the chaos, everything they owned—including enough timber for a new building—was reduced to ashes, except for a trunk containing Rs. 1,000 in silver coins, their most prized possession.

Amid the turmoil, Pi Kham Ciang sat on the trunk to protect it from being stolen. Tragically, in the process, she sustained burns on her arms, an injury that jolted her awake from the frenzy. Her quick thinking saved the family’s most critical asset despite the devastating loss.

Rebuilding of Pu Pau Suan’s House

Using the silver coins saved from the fire, Pu Pau Suan purchased corrugated roofing sheets, along with the rafters and beams originally used for Fort White Hospital, and began constructing a two-story house. Because these materials adhered to British standards, the resulting structure stood out as the finest in the community.

The upper floor featured a worship room, three bedrooms, and a hall. The lower floor included a spacious sitting room, known as the mailim, and a versatile area, called the innpi, which also served as a granary. On special occasions, the mailim was reserved for men, while the innpi was designated for women.

Adjacent to the main building were a large kitchen, a spacious dining room, firewood storage, and a sumbuk for pounding grains. Each floor was equipped with common restrooms, adding to the convenience and functionality of the household.

Three Doltial with a Tuangdung

The house featured three teak platforms (doltial)—one at the back and two at the front. The two front platforms were on different levels: the lower aligned with the house floor and the upper raised by 7 inches. Each doltial measured 12 by 42 feet and was connected by a 3-by-24-foot raised walkway (tuangdung), elevated 14 inches above the lower doltial and 7 inches above the upper.

A 3-foot-high railing surrounded the platforms, supported by posts with wooden beams passing through three holes. Designed to host large gatherings for special occasions, the tuangdung and doltials were enclosed with railings on three sides, with the east side open to a multi-purpose ground, known as leitual.

If Not for the Fire

In Khuasak, only four two-story buildings stood out, owned by Pu Pau Suan, Pu Thuam Hang, Pu Khai Vum, and Jamadar Tun Zam. However, none surpassed Pu Pau Suan’s house in size and facilities. Had his original house, along with the timber stock for a new one, not been destroyed in the fire, his new home would have been even more impressive.

Double Wedding in the Rebuilt Home

On November 23, 1926, a double wedding was held for Rev. Lian Zam and his younger brother, Saya Vai Khaw Htang, in the newly rebuilt house. The three bedrooms were designated as follows: the northern room, closest to the restrooms, for Pu Pau Suan; the middle room for Saya Vai Khaw Htang; and the southern room, next to the worship area, for Rev. Lian Zam. A large hallway connected the bedrooms, worship area, and restrooms.

To ensure an orderly entrance, the two brides entered the grooms’ house according to a prearranged schedule. Pi Thang Khaw Cing (120-23), daughter of Pu Thuam Ngin (120-22) and Pi Cing Zam (164-21) from Len Teng Bawng, Suum Niang Tuu, Thuk Lai Suanh, Vang Lok Khang, Pumva village, and bride of Rev. Lian Zam, entered first. She was followed by Pi Dim Lian (65-21), daughter of Pu Lun Son (65-20), and Pi Huai Hau (121-21) from Khum Thang Tuu, That Lang Suanh, Nge Ngu Khang, and bride of Saya Vai Khaw Htang from Khuasak. Regarding the double wedding, Pu Pau Suan composed a lyric:

“Von ngualkoai tu, lia nguallai pan, Ka dei ci bang teal ing e;

Dei taang ci bang ka teal ni ngeal, Tai ni khat zial thiam ing e.”

Translation:

“From maidens fair, a choice was made,

For my dear sons, two brides arrayed.

As seeds are picked, the choicest rare,

So too were chosen, wives most fair.

Two unions joined with love and care.

Am I not wise, this truth to say,

To mark both bonds in one bright day?”

Ken Entrusts the House to Dr. Lian and Its Emptiness

Due to the frequent relocations required by Ken’s ministerial role, on October 9, 1972, he entrusted his house to his uncle, Dr. Vum Za Lian, the only son of Pu Pau Suan’s second marriage. The house had been unoccupied since early 1964. However, once a year, Ken carried out cleansing and maintenance. Dr. Lian and his family, including Pi Son Khaw Dim, lived there for two decades until 1991, when they emigrated to the United States. The house then remained empty for over a decade.

Donation and Reconstruction

In February 2004, at the request of Rev. Edward Hlawn Piang, General Secretary of the Zomi Baptist Convention (ZBC)—now the Chin Baptist Convention (CBC)—Dr. Lian donated the house to serve as the CBC headquarters in Falam. In early May 2004, Rev. Hlawn Piang, along with Rev. Boi Hoe (Treasurer) and Rev. Hang Khan Nang (Secretary of Evangelism & Missions), traveled to Khuasak to dismantle the house. A new two-story building was constructed later that year and named “Pu Pau Suan Villa” at the CBC headquarters in Falam. However, it neither matched the size nor the style of the original home. Like the second temple in Jerusalem, those who remembered the former house could not help but weep at the contrast.

A Hope for Rebuilding

Ken feels the same way. If Pu Pau Suan could see the building today, he would surely say, “It is not like my house.” Ken hopes that his uncle, Dr. Lian, and his family will soon rebuild a beautiful house in Khuasak in honor of Pu Pau Suan.

A Search for Blessings

Many people from various areas visit Pu Pau Suan’s tomb and search for the house, but the house no longer stands. The space where it once stood is now empty, yet people continue to seek the Lord’s blessings, hoping that the first convert can still bring blessings upon them. 38

Though Alone, Pu Pau Suan Never Fears

“The greatest want of the world is the want of men—men who will not be bought or sold; men who in their inmost souls are true and honest; men who do not fear to call sin by its right name; men whose conscience is as true to duty as the needle to the pole; men who will stand for the right though the heavens fall.”

– Ellen G. White, Education, p. 57.

Pu Pau Suan embodied these words. He was not afraid “to be drowned in the spittle-dish of society” or “to be an object of one thousand pointing fingers,” as the Myanmar saying goes. Likewise, the Chin saying compares such scorn to being “a dog with excrement on its head.” Despite the ridicule, Pu Pau Suan remained unshaken. He courageously embraced the risks associated with becoming a reformer.

Pioneering Reforms

- Endogamy: He introduced phuungkhawm by marrying one of his fifth cousins, breaking social norms.

- Christian Conversion: Pu Pau Suan became the first Christian convert in a society that vehemently opposed Christianity.

- Ritual Animal Slaughter: He prohibited lamtak – sa-ngaw, the practice of slaughtering animals at funerals.

- Bride Price: He abolished the traditional bride price at weddings.

- Double Wedding: He organized a groundbreaking double wedding for his two sons on the same day. 39

Rooted in Scripture

Pu Pau Suan’s motivation for these reforms stemmed from Matthew 11:28-30:

“Come to me, all you who are weary and burdened, and I will give you rest. Take my yoke upon you and learn from me, for I am gentle and humble in heart, and you will find rest for your souls. For my yoke is easy and my burden is light.”

He believed that the animistic traditions of his society imposed heavy burdens, particularly through the slaughtering of numerous animals during sickness, death, weddings, and festivals such as ngal-ai, sa-ai, tong. Pu Pau Suan’s reforms sought to lift these burdens and bring freedom to his people. 40

A Man of Prayer

Not only in Pu Pau Suan’s days but even in our youth, the devils were powerfully active. At one point, Pu Ngaw Kam was wrestled and dragged back down the hill, preventing him from entering Khuasak village. A man from Khuasak, who professed to be a friend of the devils, recounted his experiences in killing and eating people. Fortunately, he also revealed that the devils were afraid of the Bible, singing, and prayers.

In response, Pu Pau Suan prayed for those afflicted, including the sick and those who screamed in their dreams out of fear. The sounds of Chin musical instruments, such as drums, mithun horns, and gongs of various sizes, echoed from places like Munsia and Lunglun, said to be made by the devils. As Paul said, “Our struggle is not against flesh and blood.” (Eph 6:12).

During World War II, Pu Pau Suan arranged three underground cellars in our compound. When fighter planes dropped bombs, he commanded his family to hide in the nearest cellar while he cried out to God in prayer, seeking protection for his family, relatives, church members, and villagers. 41

As an Innovator

In the past, the responsibility for improving quality of life often fell to missionaries, and the first convert, Pu Pau Suan, followed suit. Christianity introduced civilization, with Christian leaders promoting better species of plants and animals. The tireless efforts of my parents, Pu Vai Khaw Htang and Pi Dim Lian, along with the moral support of my grandfather, established horticulture, gardening, and dairy-cattle breeding as the backbone of our family’s livelihood. These practices became models for many to emulate.

When we were young, from November to March, cattle, ponies, and goats roamed freely. The gates were opened each morning, allowing them to go to the pastures on their own, and they would be led back home in the evening. This practice was known as nganpoai—giving freedom to animals. While it was convenient, it negatively impacted our summer crops, horticulture, and gardening. In response, my father and grandpa decided to fence our Ciikpi plantation. 42

Additionally, my grandfather and my father invented a wooden machine to produce sugar cane juice and homemade cane sugar.

Pu Pau Suan: A Blender, Not a Soloist

A humorous story is told about Pu Pau Suan and Pu Thuam Hang, the first two converts, who were asked to perform a special number at the convention in 1949. They agreed to sing the hymn,

“To the Work, to the work!

We are servants of God…

Toiling on…Let us hope, …Let us watch…

and labor till the Master comes.”

However, they could not agree on the language in which to sing. Pu Pau Suan, who had learned only Myanmar, proposed that they sing in that language, but Pu Hang, who was proficient in both Myanmar and Siyin-Chin, insisted on singing in Chin.

As a result, both sang the hymn, but Pu Pau Suan could only join in at the chorus, humming along to all the stanzas while smiling at his lovely audience. In this sense, my grandfather was not a soloist but rather a blender. It seemed as though he was singing the second part, much like what the younger generations do today. Pu Pau Suan truly loved teamwork. 43

Why the First Convert Was Never Ordained

Many have inquired why Pu Pau Suan was not ordained while Pu Hang was. According to a letter from Saya Shwe Zan to Rev. Dr. E.H. East dated July 25, 1904, the first contact between Pu Hang and Saya Shwe Zan occurred on that day. Saya Shwe Zan noted, “Pau Suan had given up his bad habits, and his wife, son, and mother accompanied him every time he came to me to worship God.” This suggests that grandpa’s attendance at worship was a routine practice that likely began well before his recorded conversion on July 10, 1904. Although we do not know the exact duration of his worship with Saya Shwe Zan prior to his conversion, it is plausible that it spanned weeks or even months. Pu Pau Suan had longed for a better religion, much like Nathaniel prayed under the fig tree (Mt 5:6; Jn 1:48). 44

Pu Pau Suan: The Andrew Model

Andrew and Peter were brothers. After leaving John the Baptist, Andrew and the other disciple, John (the brother of James), became the first disciples of Jesus (Jn 1:35-42). Although Peter was summoned by Andrew, he soon became part of Jesus’ inner circle alongside James and John (Mt 17:1; 26:37; Mk 5:37). Peter was eventually recognized as “the apostle to the Jews,” much like Paul became known as “the apostle to the Gentiles.” However, Peter’s esteemed position in the inner circle and his prominence as the apostle to the Jews did not make him the first disciple of Jesus—Andrew’s role as the first could never be changed.

Similarly, Pu Pau Suan’s place as the first convert could never be erased, regardless of whether he was officially ordained or the length of his paid service.

Like Andrew, Pu Pau Suan – though less popular than the ordained Pu Hang—made equally significant contributions. While Andrew’s role was less prominent, it was vital; he lived an ordinary yet exemplary life as a soul winner (Jn 1:41) and a motivator (Jn 6:8, 9). For example, when the Greeks approached Philip, saying, “Sir, we would like to see Jesus,” Philip turned to Andrew, not Peter (Jn 12:20 NIV). Andrew consistently chose service over prominence, filling gaps without seeking recognition, and Pu Pau Suan embodied this same model of humble, impactful service. 45

Teamwork of the First Two Converts

The teamwork between Grandpa and Pu Hang can be likened to two boatmen, each with an oar: Pu Hang at the front and Grandpa at the rear, steering the boat. Whether ordained or not, their collaboration was crucial, with each playing an essential role in their respective positions, leading to their shared success. 46

Termination of Pu Pau Suan’s Service

Had his service not ended early due to a lack of funds and deteriorating eyesight, Pu Pau Suan would likely have been ordained alongside his colleagues. Despite this, as a man of vision, he continued God’s work as a layman and volunteer until his death. As the Burmese saying goes, “A jewel in the mud does not lose its value.” Likewise, Pu Pau Suan’s worth remained unchanged—ordained or not, paid or unpaid—he lived fully for the God he believed in. The people he served held him in deep affection. 47

The Writer Visits Thangnuai

First Visit:

When I visited Thangnuai in 1995, I was welcomed as if my grandfather himself had returned. They prepared a welcoming gate and even had a mithun ready to be slaughtered, which I declined as a vegetarian. They showed me the empty plot where my grandfather’s house once stood and the spring fountain he had used. Their warm hospitality deeply touched me, filling me with nostalgia.

Pu Hang Suan: The First Convert from Thangnuai

Second Visit:

The next time I visited Thangnuai was in 2006, for the Centennial Celebration commemorating the baptism of Pu Hang Suan on May 12, 1906. I was invited as a special guest in honor of my grandfather. Although I had become an Adventist, their love for me remained unchanged. I preached a sermon on Matthew 11:28-30, my grandfather’s favorite passage, and gave a seminar on rural development. In appreciation, I was presented with a ten-span aluminum pot, embossed with the names of Pu Pau Suan and “Thangnuai Centennial 1906-2006.“

The believers of Lophei village had loved my grandfather as their own father. When Khuasak was bombed by a fighter plane, Pu Pau Cin from Lophei arrived before any of my grandfather’s family members had even emerged from the cellars, asking if anyone had been hurt or killed. 48

Pu Pau Suan as a Fundamentalist

The first converts were fundamentalists, observing Sunday with a strictness surpassing even modern Seventh-day Adventists’ Sabbath observance. While resting in his hunting tent, Pu Pau Suan saw a bucking deer unexpectedly stop nearby. Acting on impulse, he shot it but later regretted the act, blaming his poor eyesight. They practiced kneeling prayer and refrained from using ornaments.

Reflecting on Dr. Simon Pau Khan En’s view of the progression of Christianity among the Chins, I believe Pu Pau Suan and Pu Hang would express concern about the influence of worldliness and materialism in the church today. They would likely urge a return to the Bible and the principles they upheld, particularly before the Golden Jubilee in 1954. 49

The End of an Era: The Passing of Pu Pau Suan

Death is inevitable, as seen since the days of Adam. Even great patriarchs like Abraham and David had to go the way of all the earth. So it was with Pu Pau Suan, who, after 76 years of life, fulfilled his mission of leading his people from the darkness of animism to the light of Christianity. His colleague Pu Thuam Hang, his son Rev. Lian Zam, and his beloved wife Pi Kham Ciang had preceded him. After months of suffering from stomach pain, he passed away peacefully on March 3, 1951 survived by his loved ones, the family of Rev. Lian Zam, Saya Vai Khaw Htang and his wife, Pi Son Khaw Dim with his youngest son Dr. Vum Za Lian (D. Mn.) who just turned five years and many relatives and believers.

Conclusion

Dear fellow people of God, let us reflect on the changes from 1954 through the Diamond Jubilee in 1979 and the Centennial in 2004. The 120th Anniversary in 2024 has passed without celebration due to the current situation. What trends lie ahead? Jesus is coming soon. He asked, ‘When the Son of Man comes, will He find faith on the earth?’ (Luke 18:8, NIV).

What has set Christians apart as the elite among the Chins? God answers, “Those who honor me I will honor” (1 Sa 2:30 NIV). “Righteousness exalts a nation, but sin is a disgrace to any people” (Pro 14:34, NIV). We are called to be the heads, not the tails (Dt 28:13).

Cheap grace has impacted our youth, with drugs and AIDS claiming many lives that could have been saved (Pro 22:6). As leaders and parents of our people, we bear the responsibility. Let us pray for the healing of our land (2 Ch 7:14) and commit to mending our ways.

“Seek the LORD while He may be found” (Isa 55:6). May the grace of the Lord Jesus be with you during this Centennial celebration. Heaven is our goal; let us meet at Jesus’ feet. “Come, Lord Jesus! Amen.”

About the Writer

Kenneth Htang Suanzanang (Ken) is the grandson of Pu Pau Suan, a renowned reformer, and Pi Kham Ciang, who became the first Christian converts in the Chin Hills in 1904. His parents, Pu Vai Khaw Htang and Pi Dim Lian, were diligent and hardworking, supporting Pu Pau Suan’s large family. Ken’s father, after completing 6th Standard at the Khuasak ABM School, went on to serve as a teacher in various locations, including Khuasak, Thuklai, and Mualbem. In this role, he educated many individuals who later became gazetted officers in civil and military sectors, as well as political leaders among the Siyin-Chins.

Ken’s Sibblings Include

Ciang Khaw Lian, married to Hav./Sgt. Hang Khaw Lian; Hau Za Dim, married to Capt. Suang Za Khai; Ciin Khaw Hau, married to Capt. Sawm Hang, Chairman of the 4th Tiddim Township Peoples’ Parliament [Pyithu Hlutdaw]; Suan Huai, who passed away as a baby; Lun Khan Dim, married to Sgt. Clk. Tuang Za Nang (separated); Zam Za Cing, a nurse, married to Pastor Cin Ngaih Pau; and Kenneth H. Suanzanang, the youngest, who is the only son.

Ken’s Life and Legacy

Ken was baptized on December 8, 1962, and began his ministry as a teacher on May 10, 1963, becoming the third generation in his family to serve God. He graduated from MUAS in 1969 and married Lian Za Dim, the daughter of Pu Awn Cin, chief of Thuklai, and Pi Ciin Kam, on January 5, 1970. Ms. Lian Za Dim later served as a teacher and as the director of the Ministries for Children, Women, and Family of Upper Myanmar Mission (UMM).

Ken was ordained on December 13, 1980, and has served the Lord in various roles, including teacher, pastor-evangelist, church pastor, pastor-architect, district pastor of the Mandalay Region, principal of UMAS, country director of ADRA Myanmar, administrator of the Yangon Attached District, and president of the Upper Myanmar Mission. He also directed the Departments of Communication, Legal Affairs, Public Relations, Religious Liberty, and Chaplaincy Ministries.

After his retirement in 2008, Ken received two prestigious awards from the Seventh-day Adventist Church’s World Headquarters: ‘The Award of Merit’ from Adventist World Radio in December 2009 and the ‘Adventist NetAward’ from the Communication Department in May 2011.

As a development worker, Ken spearheaded various projects, including gravity-fed water systems in the villages of Hiangzing, Bualkhua, Zampi, Lezang, Old & New Sunthla, Cerhmun, Old & New Saltaung, and Langli. He also implemented tube wells at hospitals in Yenantha, Kalemyo, Myaungmya, and 70 tube wells in the Ayeyarwady Division. His contributions extended to the rehabilitation of the Yenantha Leprosy Hospital, Thamaing Rehabilitation Hospital, the Burn Unit Center at Yangon Children’s Hospital, and the Fort White Hydroelectric Project for Khuasak and Thuklai.

Children of the Writer

- Lian Huai has served in various roles at ADRA Myanmar, including receptionist, office secretary, accountant, treasurer, and HR director, before also holding the HR director position at BRAD and currently at World Vision. She is married to Soe Thura Htwa, and they have two daughters: Jennifer DimSaan Htwa, who will complete her second year of B.Sc. Nursing at Adventist International University (AIU) in Bangkok, Thailand, in June 2025, and Angela PauSaan Htwa, who will begin her second year at the School of Medicine, University of Cyberjaya, Malaysia, in August 2025.

- Kam Uap passed away at the age of 4 years and 7 months.

- Thang Pau, a musician, served at Adventist World Radio Myanmar in various roles, including volunteer, assistant technician, technician-engineer, and studio supervisor in Yangon and Pyinoolwin. He later taught at Yangon Adventist Seminary (YAS) and became the IT & Media Services Supervisor for the Myanmar Union Mission. Esther Po, also a musician, initially served at AWR in Yangon and now serves as the choir conductor at YAS. They have two children: Samuel Nang Pau, who will complete his third year of B.Sc. Nursing at Adventist University of the Philippines (AUP) in March 2025, and Rhoda D. Pau, who will begin Grade 10 at Yangon Adventist Seminary (YAS) in June 2025.

The grandchildren of Ken represent the fifth generation of workers, continuing the legacy of their great-great-grandfather, Pu Pau Suan.

References:

- The Chin Hills Vol. I by Carey and Tuck (Carey-Tuck) page 20; & Chin Christian Centenary Magazine 2004 (CCCM 2004) page 240.

- Captain K. A. Khup Za Thang, Genealogy of the Zo (Chin) Race of Burma pages 66-77.

- U K.T. Ngo Za Lian: Unpublished Manuscript.